Moulton Design Influences

Beginnings

On this page you will read things about Moultons that you have not seen anywhere else. I don't want to go scurrying around checking facts and dates in books to repeat work that others have already done. I want to write the whole thing right off the top of my head. I will try to put across my view of what have been the significant influences upon the design of the Moulton. All designers absorb ideas from everything they are surrounded by whether they realise it consciously or not. Alex Moulton was like a jackdaw in that he borrowed and stored away many different design features, combined them and blended them to get the result he was after. There are several features about his early bicycle designs that can be traced back to influences that were feeding into the creative work. It is fun to explore these contributions.

Petrol Rationing

Firstly, a little background. In 1956 there was a blockade of the Suez canal, an immediate fuel crisis and petrol rationing. Even if this had not happened, road transport soon after the last war was mostly very frugal. Bubble cars were popular and the Mini was being planned. The Morris Mini that is, not the Moulton Mini. So, to save money or just to save their fuel allowance, people were thinking of cycling. However, most bicycles did not have the sexy image than they enjoy today. Alex Moulton "borrowed" (he never gave it back) an expensive lightweight touring bicycle, a "curly" Hetchins, and was astonished at how much more pleasurable it was to ride than the old irons of his youth. This was mostly due to the Hetchins quality and light weight, and probably helped by the gearing and tyres. Significantly, the tubes were chrome-plated rather than painted, a specification that Alex would later adopt for the top-of-the-range S class Moultons. Also, the Hetchins has the very ornate lugwork at the brazed joints. Moulton, being essentially concerned about function rather than decoration, rejected the idea as a kind of pointless craftsmanship.

Alec Issigonis and the Mini

Working on the Mini with his good friend and fellow designer Issigonis reinforced Alex's no-nonsense, functional approach. Brilliant simplicity, innovation and audacity were their tenets. The design had to fizz with novelty, but the novelty had to be genuinely far better than what was being done previously. This was the case with the Mini. It was perfect for its purpose nearly straight away. They hardly needed to change it in 50 years of manufacture. It did some things, such as rallying, better than their wildest dreams. In large part this was down to Moulton's rubber suspension. So as a result, he had supreme confidence as a designer. He only had to choose something to develop and he could make a tremendous success of it. And that something, he had decided, was the bicycle.

We should realise that although we may think of Alex Moulton as being staid, in his younger years he clearly cut a dash. He was into travelling at speed from an early age using sports cars, motorcycles and power boats. He liked dynamic excitement. When it came to designing a bicycle there was from the outset an aim to make the design efficient and fast.

So where to start? The Mini had small wheels, so the new bicycle would have small wheels. The Mini was for everyone, old and young, families, men and women, people of status and the great unwashed, so the bicycle would follow this egalitarian approach. It was to be truly classless and unisex. And like the Mini, it would have to be absolutely revolutionary. It had to be as good as the Mini, if not better. Alex's reputation depended upon it. He had a number of small models made to give a real idea of how he anticipated the bicycle would look. Importantly, all these models depend on the "frame" being made as a monocoque, that is, rivetted-together bodywork made from sheets of aluminium.

But hold on a minute. Granted the Mini was a major influence, but I think more in terms of attitude and execution. There is a vehicle much closer to the original concept of the Moulton bicycle. A two wheeled vehicle putt-putting around all over Europe, simple, stylish, very innovative, born of necessity and most importantly, making use of a monocoque frame. That machine was the Vespa scooter. Compare these photos with the models above. Now, Alex Moulton knew all about motorcycles and scooters. He had been motorcycling for years, several times riding down to the south of France. He had also spent quite a bit of time in Italy and was good friends with the Italian designer Pininfarina. Indeed, Pininfarina designed the cowling for one of the first prototype Moulton bicycles, which is still kept in the museum.

But hold on a minute. Granted the Mini was a major influence, but I think more in terms of attitude and execution. There is a vehicle much closer to the original concept of the Moulton bicycle. A two wheeled vehicle putt-putting around all over Europe, simple, stylish, very innovative, born of necessity and most importantly, making use of a monocoque frame. That machine was the Vespa scooter. Compare these photos with the models above. Now, Alex Moulton knew all about motorcycles and scooters. He had been motorcycling for years, several times riding down to the south of France. He had also spent quite a bit of time in Italy and was good friends with the Italian designer Pininfarina. Indeed, Pininfarina designed the cowling for one of the first prototype Moulton bicycles, which is still kept in the museum.

It seems unfeasible that the massive popularity of the Vespa scooter in the 1950's would have made no impression on Alex. It was so successful because although it was made to sell at a budget price, the brilliance of the design meant that it also worked well, was tough and reliable. And very beautiful. Very significantly it had a step-through frame and small wheels, a huge advance over the traditional motorbike in terms of user-friendliness. This is what the new bicycle needed to improve upon the diamond frame.

Unfortunately, when the same principles were adopted on the design of the bicycle, Moulton soon ran into trouble. A Vespa has the engine fitted into the rear cowling and the rear wheel attaches directly to it. There is no chain drive. This means that all of the transmission forces are contained within the engine structure, which is strong. All the monocoque frame needs to do is provide a seat to sit on and a rigid connection to the steering. The weather protection was part of a dual function of the bodyshell.

Unfortunately, when the same principles were adopted on the design of the bicycle, Moulton soon ran into trouble. A Vespa has the engine fitted into the rear cowling and the rear wheel attaches directly to it. There is no chain drive. This means that all of the transmission forces are contained within the engine structure, which is strong. All the monocoque frame needs to do is provide a seat to sit on and a rigid connection to the steering. The weather protection was part of a dual function of the bodyshell.

In a bicycle, the requirements are entirely different. The rider constantly tries to twist the whole structure by pressing on the pedals and pulling on the handlebars. There can be large forces on the bottom bracket due to hard pedalling and from there to the rear wheel due to the chain transmission. Importantly, because the bicycle would not be made from pressed steel, it would need reinforced areas around the points of high loading so that the aluminium was not fatigued. Aluminium does not like to be bent back and forward. Nevertheless, aircraft bodies are made from aluminium sheet perfectly successfully, as Moulton well knew having worked for Bristol. He therefore went ahead and had some prototypes made.

The first Moulton bicycle used 14" wheels, front suspension and a sub-frame at the back for the rear wheel. Disappointingly, it was dismantled at some stage and only the main frame exists. The appearance may seem comical now, but it should be remembered that the design was just to test the theory of a monocoque. The really exciting thing is that it looks unlike any other bicycle before or since. The ubiquitous seat tube that runs between the saddle and the bottom bracket on all bicycles, is done away with. The frame flows neatly through this area from the front to the rear, where it changes function to become a load carrier. And note the enclosed rear wheel and transmission, reminiscent of the Vespa.

The first Moulton bicycle used 14" wheels, front suspension and a sub-frame at the back for the rear wheel. Disappointingly, it was dismantled at some stage and only the main frame exists. The appearance may seem comical now, but it should be remembered that the design was just to test the theory of a monocoque. The really exciting thing is that it looks unlike any other bicycle before or since. The ubiquitous seat tube that runs between the saddle and the bottom bracket on all bicycles, is done away with. The frame flows neatly through this area from the front to the rear, where it changes function to become a load carrier. And note the enclosed rear wheel and transmission, reminiscent of the Vespa.

The first prototype had a trailing link front suspension that used rubber bands in tension as a springing medium. No photographs of this are in the public domain, yet it surely used some kind of pivoting arm, like a see-saw. Again, we find a similarity in the Vespa front suspension. It is trailing, and the suspension arm connects to a shock absorber in front of the pivot point, that is, the shock is working in tension like Moulton's rubber bands. My guess is that the bicycle used the same arrangement.

The first prototype had a trailing link front suspension that used rubber bands in tension as a springing medium. No photographs of this are in the public domain, yet it surely used some kind of pivoting arm, like a see-saw. Again, we find a similarity in the Vespa front suspension. It is trailing, and the suspension arm connects to a shock absorber in front of the pivot point, that is, the shock is working in tension like Moulton's rubber bands. My guess is that the bicycle used the same arrangement.

This prototype was ridden some distance over a period of several months, so it was not cast aside without thorough practical tests. It had great advantages in that it was much more rigid than a conventional frame and also weighed less. To me, it seems like a great start, but disappointingly, this line of development hit the buffers without any more prototyping. There have been three reasons given: Firstly, subframes were needed to carry the higher point loadings; secondly that the appearance was not attractive and thirdly that that the panels were noisy when travelling. Alex felt like the new bicycle was moving in the wrong direction. He was particularly annoyed by the creation of road noise, which he felt was an unacceptable and intrusive disadvantage.

What Finished the Monocoque?

Let's examine the three objections bearing in mind Moulton's design style. Using subframes may seem to be a compromise, but monocoque cars do it, and the Vespa's engine is a kind of subframe. The attractiveness is a problem of design; the models are not unattractive. There is the issue that the bicycle needs to be taller than the scooter because the rider is necessarily much more stretched-out. But in recent times the Moulton design has reduced the height of the seat and headtubes to scooter levels. Road noise and vibration is a more serious issue, and I think that this did kill the monocoque, for an interesting reason.

Flat panels do vibrate like a Rolf Harris wobble board to produce a sound known as drumming. But they can be stiffened by curving them. On car doors, you almost always get a pressed-in line for stiffening. If the panel has a double curvature, so much the better. The Vespa for instance has the beautiful side "blister" panels that do not produce any drumming. So, the drumming and vibration of the monocoque could have been addressed by designing them as curved surfaces. I had a go at this, and made a cardboard model. It was clearly extremely stiff, light and the cardboard felt taught and rigid. I could easily believe that this structure combined with, say, a fill of polystyrene beads, would be silent.

Flat panels do vibrate like a Rolf Harris wobble board to produce a sound known as drumming. But they can be stiffened by curving them. On car doors, you almost always get a pressed-in line for stiffening. If the panel has a double curvature, so much the better. The Vespa for instance has the beautiful side "blister" panels that do not produce any drumming. So, the drumming and vibration of the monocoque could have been addressed by designing them as curved surfaces. I had a go at this, and made a cardboard model. It was clearly extremely stiff, light and the cardboard felt taught and rigid. I could easily believe that this structure combined with, say, a fill of polystyrene beads, would be silent.

There is a defining feature of Moulton's bicycle designs that probably took root at the time of abandoning the monocoque. He does not like curves. From 1960 through to the present day all types of curves have been eliminated from his designs, to the point where even the front forks of the Bridgestone were not curved. I will say more about this later. The monocoque did not appeal to Moulton, I suggest, because it did not suit his predilection for making "bony" structures of straight rods. Perhaps he played with drinking straws as a child? If the monocoque needed curved surfaces to look attractive and work quietly, it was no bloody good.

Tubes of various sizes

So, how to begin again? In this photograph, the next step; the Moulton bicycle that was used to secure the patent. It has the lovely white cowling made by Pininfarina, the design house that also worked extensively for the British Motor Company, and front and rear suspension of a very similar design. At the rear, the arrangement would eventually be simplified into the curved and tapered forks of the Series 1 production model.  At the front, the suspension is known as "Earls Type". Like the rear, the fork pivots upwards to compress a rubber block close to the fulcrum. Behind the front wheel is a very sturdy curved bar connecting the steering column with the suspension pivot fixed to its base. When the bicycle was picked up to load into a car, Moulton observed that the wheel steered the wrong way when the bicycle leaned over sideways. The weight of the heavy bar pulled it. He swiftly abandoned the Earl's Type suspension for this reason.

At the front, the suspension is known as "Earls Type". Like the rear, the fork pivots upwards to compress a rubber block close to the fulcrum. Behind the front wheel is a very sturdy curved bar connecting the steering column with the suspension pivot fixed to its base. When the bicycle was picked up to load into a car, Moulton observed that the wheel steered the wrong way when the bicycle leaned over sideways. The weight of the heavy bar pulled it. He swiftly abandoned the Earl's Type suspension for this reason.

I do think that Alex's rejection of his first front suspension was in the pipeline long before that fateful steering swivel. The reason is this: he likes delicacy in design. You see it through the entire history of his design work, from the dinky suspension units on the Austins Mini and 1100, through the spaceframe lattice chassis and slender window frames of the Moulton coach, to the fabulous intricacy of the New Series pylons. On the Pininfarina Moulton bicycle, Alex debuts his first use of thin tube on both sets of forks, a technique that would become his defining design style. It must have annoyed him no end to have to fit this delicate structure to such a thumping tube, and not only that, a curved tube to boot. Out with curves!

The Evolution of the Bicycle

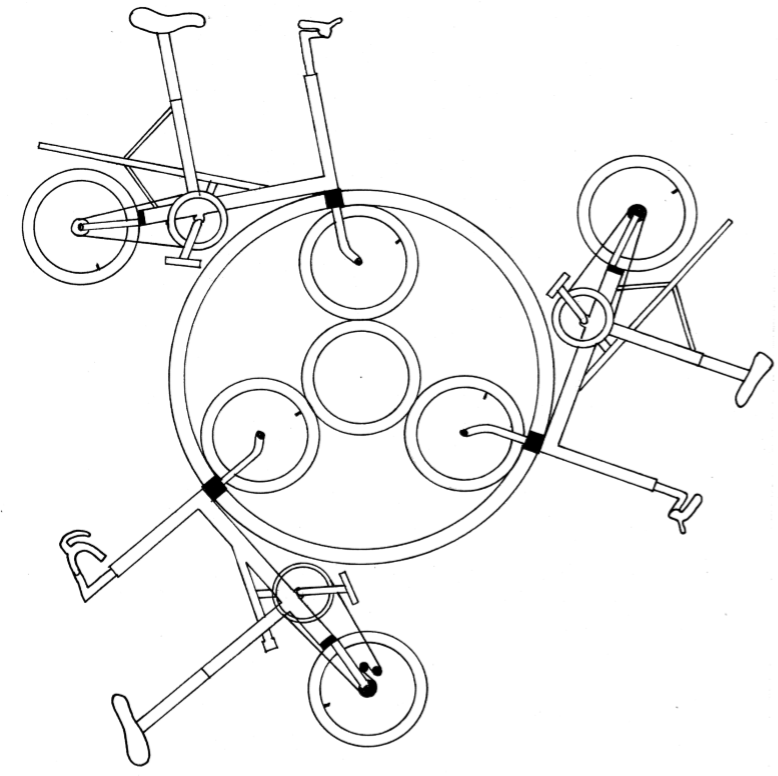

Now I have to back my truck up a little way to include some interesting drawings. They are titled "Evolution of the Bicycle" and originated at the Moulton Developments drawing office. Note Alex's confidence that bicycle design as a whole would be changed, not just added to. At that time he did not anticipate the intransigence of the UCI nor the invention of the mountain bike. All of the drawings are on one piece of paper and the top four bicycles are existing designs, as of 1960. There is a classic Starley diamond frame bicycle with 26" wheels, two other more radical big wheelers and a small-wheel bicycle designed by Raleigh. Below that are 5 drawings of Moulton's own bicycle designs. I will omit the classic machine- we all know what that looks like. Suffice to say, the very obvious feature is that it is built around triangular shapes made from round section tubes.

Now I have to back my truck up a little way to include some interesting drawings. They are titled "Evolution of the Bicycle" and originated at the Moulton Developments drawing office. Note Alex's confidence that bicycle design as a whole would be changed, not just added to. At that time he did not anticipate the intransigence of the UCI nor the invention of the mountain bike. All of the drawings are on one piece of paper and the top four bicycles are existing designs, as of 1960. There is a classic Starley diamond frame bicycle with 26" wheels, two other more radical big wheelers and a small-wheel bicycle designed by Raleigh. Below that are 5 drawings of Moulton's own bicycle designs. I will omit the classic machine- we all know what that looks like. Suffice to say, the very obvious feature is that it is built around triangular shapes made from round section tubes.

Here is the Crescent Folding Bicycle of 1960. It has no triangular main frame and the tube section is a flattened oval. Both of these things are influential, particularly the tube shape. The flatter shape from above looks more slender, yet from the side we accept that it has to be broader for strength, so it appears more elegant than say, a wide diameter round tube. All of the classic Moultons used a flattened oval. The fact that the bicycle folds is an important seed planted in Moulton's mind that was later to germinate so powerfully.

Here is the Crescent Folding Bicycle of 1960. It has no triangular main frame and the tube section is a flattened oval. Both of these things are influential, particularly the tube shape. The flatter shape from above looks more slender, yet from the side we accept that it has to be broader for strength, so it appears more elegant than say, a wide diameter round tube. All of the classic Moultons used a flattened oval. The fact that the bicycle folds is an important seed planted in Moulton's mind that was later to germinate so powerfully.

Here is what Raleigh were doing at the time. By 1960, Raleigh were aware that Alex Moulton was working on a small wheeled bicycle. In fact, we will see the drawing of the Mk4 prototype that was shown to them further down the page. Note the month of "March" written forcefully under the year date, as if there might be some wrangling over who had got there first.

Here is what Raleigh were doing at the time. By 1960, Raleigh were aware that Alex Moulton was working on a small wheeled bicycle. In fact, we will see the drawing of the Mk4 prototype that was shown to them further down the page. Note the month of "March" written forcefully under the year date, as if there might be some wrangling over who had got there first.

Back to the Raleigh machine; apart from the wheel size it is clear that they are going in a very different direction to Moulton. The main frame follows the pattern of the early Lambretta scooter in using a curved tube. It's simple, but not very rigid. Even at that stage, Raleigh were thinking along the lines of utility and not performance. My guess is that they responded to Moulton's research with a design of their own, cribbed directly from the Lambretta. Thirty years later this frame design, with a dodgy hinge in the middle, replaced the best-selling Raleigh Twenty. Thousands were imported ready made and simply fitted with components in Nottingham. It had the merit of low-cost, but little else.

This is the Cross-Frame bicycle designed by Sir Alliot Verdon-Roe in 1952. He was the same A. V. Roe who founded Avro Aircraft. Later he went to Cowes, bought Saunders' boatbuilding yard and founded Saunders - Roe. That company went on to build the first hovercrafts. He was a supporter of Oswald Moseley in the '30s, then both his sons were killed in the War. A.V. Roe died in 1958 so he drew his bicycle design as an old man in retirement. He may have had in mind the frame shown in the photo below that uses tensioning cables in place of the crossbar, downtube and seat stays. It is interesting to compare the saddle position and relaxed frame angles of both bicycles. But Verdon-Roe dispenses with the cables, possibly thinking of the wing spar of an aircraft.

This is the Cross-Frame bicycle designed by Sir Alliot Verdon-Roe in 1952. He was the same A. V. Roe who founded Avro Aircraft. Later he went to Cowes, bought Saunders' boatbuilding yard and founded Saunders - Roe. That company went on to build the first hovercrafts. He was a supporter of Oswald Moseley in the '30s, then both his sons were killed in the War. A.V. Roe died in 1958 so he drew his bicycle design as an old man in retirement. He may have had in mind the frame shown in the photo below that uses tensioning cables in place of the crossbar, downtube and seat stays. It is interesting to compare the saddle position and relaxed frame angles of both bicycles. But Verdon-Roe dispenses with the cables, possibly thinking of the wing spar of an aircraft.

In many ways his design is quite brilliant and revolutionary, and I think that it can be regarded as the main influence on the early Moulton "Lazy F" frame. For one thing, it is audacious- completely cheeky. Every triangle in the structure of the Starley design has been consciously abandoned. Moulton loves audacity in design. Doing things in a new way, throwing away established tenets but actually coming up with something better, is his hallmark. No pun intended. Rear fork blades that extend directly to the axle; tapered and flattened oval tube; what would have to have been some kind of pierced joint at the cross; utter functionality and simplicity; a low seat tube with a long, tapering seat post; bottom bracket welded on to the bottom of it's own tube. These features must have attracted Alex greatly, because he used them all.

In many ways his design is quite brilliant and revolutionary, and I think that it can be regarded as the main influence on the early Moulton "Lazy F" frame. For one thing, it is audacious- completely cheeky. Every triangle in the structure of the Starley design has been consciously abandoned. Moulton loves audacity in design. Doing things in a new way, throwing away established tenets but actually coming up with something better, is his hallmark. No pun intended. Rear fork blades that extend directly to the axle; tapered and flattened oval tube; what would have to have been some kind of pierced joint at the cross; utter functionality and simplicity; a low seat tube with a long, tapering seat post; bottom bracket welded on to the bottom of it's own tube. These features must have attracted Alex greatly, because he used them all.

I initially thought that the cross-frame bicycle was really more a design exercise than a real machine, but recently I have discovered a fascinating Pathe film of Alliot Verdon-Roe riding it backwards around his garden at Rowlands Castle, at the age of 80! In addition, he demonstrates an aluminium-clad "Bi-car" that is a cross between a motorcycle and a car. It precedes Alex's monocoque slightly, and looks rather like it. Whether the two men were acquainted, I do not know, but is clear that Verdon-Roe's creativity spurred Moulton on to make his own designs work in solid form.

You can see the Pathe film here.

Here again we see the date given, 1960, and "March" clearly added later. I am not sure what can be read into this, but it is interesting that the time is so emphatically recorded. This machine was the one that was developed for Raleigh when they were in negotiations with Moulton. I recall Alex's talk at Bradford on Avon in 2008 when he said that the curve of the main beam was put in because Raleigh had asked for it. Alex himself thought it risible, and never used a curved beam again. In the photograph the machine that looks most like it is fitted with a shiny black leg shield, although this is labelled Mk3. The grey bicycle behind it is actually very similar and is labelled Mk4. The museum bicycle tags do not correlate exactly with the drawings.

Here again we see the date given, 1960, and "March" clearly added later. I am not sure what can be read into this, but it is interesting that the time is so emphatically recorded. This machine was the one that was developed for Raleigh when they were in negotiations with Moulton. I recall Alex's talk at Bradford on Avon in 2008 when he said that the curve of the main beam was put in because Raleigh had asked for it. Alex himself thought it risible, and never used a curved beam again. In the photograph the machine that looks most like it is fitted with a shiny black leg shield, although this is labelled Mk3. The grey bicycle behind it is actually very similar and is labelled Mk4. The museum bicycle tags do not correlate exactly with the drawings.

There are other non-typical Moulton features, most obviously, the enormous webbed lug at the front of the bike to join the main beam to the headtube. Raleigh must have been suspicious of the aircraft construction methods that Alex was proposing for fabricating the frame, or maybe they were wedded to lugged frame construction by decades of experience. There's a similar feature at the bottom of the seat-tube. Interestingly, the rear rack is made from pressed sheet steel or aluminum, rather like the original models. A large rear bag has been drawn in, but using a dotted line. The shape has not been finalised. An elegant front mudguard completely conceals the ponderous front suspension tube. Raleigh clearly had reservations about how the curved tube would be perceived. All in all, Raleigh's influence seems concerned mostly with aesthetics and this was helpful.

The Mk5 was painted gloss black with silver front and rear forks. Perhaps at this early stage Alex was thinking about chroming parts? At first sight, this bicycle looks similar to the Raleigh model previously described, but look closer and you will see that nearly all those features that were put in at Raleigh's request have been deleted. This seems to be both a reaction and a resolution to stick to the Moulton ideals. One can only guess that the design of the Mk5 was done after Raleigh had rejected the whole concept. Note the lugless construction. At that time, only the most expensive lightweight sports bicycles were made without lugs. It shows that the new bicycle was always intended to be high-quality and lightweight. Very significantly, the main beam is made from flattened oval tube and this is the first time we see this in a Moulton design. Of course, this tube section never changed again, even to the present day.

The Mk5 was painted gloss black with silver front and rear forks. Perhaps at this early stage Alex was thinking about chroming parts? At first sight, this bicycle looks similar to the Raleigh model previously described, but look closer and you will see that nearly all those features that were put in at Raleigh's request have been deleted. This seems to be both a reaction and a resolution to stick to the Moulton ideals. One can only guess that the design of the Mk5 was done after Raleigh had rejected the whole concept. Note the lugless construction. At that time, only the most expensive lightweight sports bicycles were made without lugs. It shows that the new bicycle was always intended to be high-quality and lightweight. Very significantly, the main beam is made from flattened oval tube and this is the first time we see this in a Moulton design. Of course, this tube section never changed again, even to the present day.

Both the seat tube and the head tube are heading towards a tapered design, suggesting Moulton's desire for more delicacy. In fact, the actual Mk5 prototype is the first one that has a fully-formed tapered seat tube. The bottle-shaped head tube was seen on the Raleigh demo prototype and this is the only feature that survives. At the front, we find that the workings of the suspension are exposed and a slender mudguard fits to the moving part, i.e. the front forks. This again tends towards delicacy. Excitingly, the rear carrier is clearly designed to be removable. Even at this early stage, the concept of the Speedsix "Stripped for Action, Dressed for Travel" is part of the design brief.

Pininfarina designed the cowling for a prototype very similar to the Mk5 and the whole bicycle was painted white. It was given its own Mark, the Mk6, and is arguably the most beautiful of the Moulton prototypes. The white bicycle is always brought out as a show bicycle to represent the state of the art at that time.

Pininfarina designed the cowling for a prototype very similar to the Mk5 and the whole bicycle was painted white. It was given its own Mark, the Mk6, and is arguably the most beautiful of the Moulton prototypes. The white bicycle is always brought out as a show bicycle to represent the state of the art at that time.

This drawing appears on the A2 sheet directly below the drawing of the Mk5 prototype. I am guessing that it is a stripped down version of the Mk6 Pininfarina prototype. At the base of the seat-tube it looks as if the tube has been flared and formed into a shape that can be brazed to the main beam. The Pininfarina prototype has this feature and that is actually what they eventually did in production. There are a few detail differences with the Mk5 that are interesting, but these are possibly just ways of saying "We could do this joint in a different way", for example. A pierced tube joint is shown at the front of the bike. This would be the first pierced tube joint ever to be used in a mass-produced bicycle frame. If the cowling was not in the way of all photos of the Pininfarina, we could correlate this detail.

But the remarkable feature is that the fairing and rear carriers are removable. As early as January 1962, the new bicycle was being raced around the track at Southampton. In the Mk5 and the Mk6, Moulton was clearly trying to bring all possible functions of a bicycle together in one design. And he had one more arrow in his quiver; a hinge placed just at the point where the little "crossbar" handle curves down. This bicycle is the first "Stowaway". It is the genesis of his all-purpose-bicycle concept ultimately realised in 1991 as the spaceframe APB.

Here is the final drawing on the page and one that I am not certain ever made it into the solid. The astounding feature of it is the horizontal tube, again a flattened oval. At each end, this is edge-brazed to the head and seat tubes respectively. You may say, "It was just a design exercise" but it demonstrates clearly that Moulton does not mind the discontinuity of the Z shape. In fact, when he was commissioned to work on a reinterpretation of the classic Moulton for Bridgestone in 2000, he produced something that echoed the Z shaped form.

Here is the final drawing on the page and one that I am not certain ever made it into the solid. The astounding feature of it is the horizontal tube, again a flattened oval. At each end, this is edge-brazed to the head and seat tubes respectively. You may say, "It was just a design exercise" but it demonstrates clearly that Moulton does not mind the discontinuity of the Z shape. In fact, when he was commissioned to work on a reinterpretation of the classic Moulton for Bridgestone in 2000, he produced something that echoed the Z shaped form.

The Bridgestone frame is aluminium and has characteristic TIG welding at the joints. It's a high-quality machine of course, but seems very functional more than beautiful, a design for mechanical engineers. It has a small version of an aircraft landing gear hinge to connect the front forks to the steering. The modern bicycle that most represents how the design of the Z frame could have been successful is the German "Birdy" made by Riese and Muller. The resemblance is so obvious that anybody seeing the Z design and knowing the Birdy would immediately make a connection. I thought it highly unlikely that either Riese or Muller would have ever set eyes on Moulton Developments Limited Drawing MD-490 but German Moultoneer Marco Schuett assures me that the Birdy was indeed culled from Moulton's design.

The Bridgestone frame is aluminium and has characteristic TIG welding at the joints. It's a high-quality machine of course, but seems very functional more than beautiful, a design for mechanical engineers. It has a small version of an aircraft landing gear hinge to connect the front forks to the steering. The modern bicycle that most represents how the design of the Z frame could have been successful is the German "Birdy" made by Riese and Muller. The resemblance is so obvious that anybody seeing the Z design and knowing the Birdy would immediately make a connection. I thought it highly unlikely that either Riese or Muller would have ever set eyes on Moulton Developments Limited Drawing MD-490 but German Moultoneer Marco Schuett assures me that the Birdy was indeed culled from Moulton's design.

Alex Moulton had made a terrific amount of progress in a very short time. The drawing of the Mk1 prototype is dated August 1959 and the Mk6 is October 1960. These prototypes capture that very fruitful period and show how all the main features of the frame became fully-formed. Although function has definitely been placed before form, we can assume that the Z frame was rejected for the awkwardness of its broken tube lines. In fact, you could argue that it is primarily the long, low main beam of the Mk6 that makes the design a classic. It has a rising flow from the rear to the front and is purposeful. It suggests the shape of the Triumph TR2. But as we know, the Pininfarina never went into production. The small tube rear forks, an exciting feature, never materialised on the commercial machine.

Alex Moulton had made a terrific amount of progress in a very short time. The drawing of the Mk1 prototype is dated August 1959 and the Mk6 is October 1960. These prototypes capture that very fruitful period and show how all the main features of the frame became fully-formed. Although function has definitely been placed before form, we can assume that the Z frame was rejected for the awkwardness of its broken tube lines. In fact, you could argue that it is primarily the long, low main beam of the Mk6 that makes the design a classic. It has a rising flow from the rear to the front and is purposeful. It suggests the shape of the Triumph TR2. But as we know, the Pininfarina never went into production. The small tube rear forks, an exciting feature, never materialised on the commercial machine.

On the right you can see the top tube and saddle of the chrome-plated Curly Hetchins, the monocoque body shell, the Pinifarina prototype and the Series one production Moulton. Clicking on this picture will bring up a print of the last three prototype drawings as they appeared together on the page. In a note, a hinge in the frame is described, indicating that at that stage Moulton was not so rigorously opposed to folding bicycles as he later became. Ironically, Moultoneers are always indignant about the common enquiry from lay people about the possibility of the bike folding, echoing Alex's enlightened views.

On the right you can see the top tube and saddle of the chrome-plated Curly Hetchins, the monocoque body shell, the Pinifarina prototype and the Series one production Moulton. Clicking on this picture will bring up a print of the last three prototype drawings as they appeared together on the page. In a note, a hinge in the frame is described, indicating that at that stage Moulton was not so rigorously opposed to folding bicycles as he later became. Ironically, Moultoneers are always indignant about the common enquiry from lay people about the possibility of the bike folding, echoing Alex's enlightened views.

At a stroke, Alex was forced to drop the Earl's Type front suspension and design his own from scratch. I am sure that Alec Issigonis was involved to some degree at this stage because we can see a step change that owes a lot to the car industry. For instance, splined shafts and the rubber concertina boot are exactly what you find in automotive steering and driveshaft design. Moulton must have been very familiar with these components after all his work on the Mini suspension.

Having decided that all the mass of the bicycle steering had to be concentrated around the axis, Moulton chose the standard fork design but in a delicate, miniaturised form. He then knew that these forks needed to slide up and down and that control had to be carried through this sliding joint. The aircraft hinge was tried, and worked, but seemed too radical for mass consumption. The new bicycle in itself would be shock enough. No need to go raving mad.

Having decided that all the mass of the bicycle steering had to be concentrated around the axis, Moulton chose the standard fork design but in a delicate, miniaturised form. He then knew that these forks needed to slide up and down and that control had to be carried through this sliding joint. The aircraft hinge was tried, and worked, but seemed too radical for mass consumption. The new bicycle in itself would be shock enough. No need to go raving mad.

Brilliantly, his new suspension was completely concealed within the steering tube and featured a splined nylon bush fitted into the tube that engaged positively with the splines on the sprung forks. Thus control to the forks passed through this sliding joint. Nothing so sophisticated or original had ever been seen on a bicycle before. A coil spring wrapped around the main rubber column stopped it from expanding outward and jamming against the tube walls. However, since most of the load was carried by the rubber, it had a natural damping function. There was even a smaller rebound spring included to stop the forks making heavy contact with the rebound stop.

Why drop the slender-tubed trailing arm forks at the rear? Moulton must have been quite satisfied with them as he never altered the design all the way through 1960 when everything else about the bike was evolving. With the benefit of hindsight we know that the move to a single tube design didn't work out so well. Once the Earl's Type front suspension had been superseded by the more conventional looking small forks, the aesthetics of the new bicycle must have been brought into focus. The rear forks no longer matched the front ones. As the front had been visually simplified, and now appeared more acceptable, Alex probably felt that he should now do something similar for the rear. This being so, his love of thin tube structures disappeared from his bicycle designs for the next 17 years.

After a few rear fork prototypes, the familiar tapered tube forks of the production Series One were finalised. Surprisingly, Moulton decided to put a curve in these fork blades to echo the front forks. He said that people would expect to see forks of this conventional curved profile. There is no doubt that visually, the Series One rear forks are the prettiest design, complementing the frame perfectly and leading the eye in a smooth swoop down the bicycle from front to back. However, it is well known that the forks can crack if treated harshly; the delicacy was taken slightly too far and the testing not severe enough. Moulton blamed the curved tubes and when the forks were redesigned for the Series Two, the curve was eliminated. There's no doubt that Series Two forks are more matched to the loads expected of them, but I've found that some well-located strengthening plates on the Series One forks makes them rigid, and sufficiently strong. In my view the vulnerability to cracking has got more to do with their low resistance to twisting than curves in the blades.

After a few rear fork prototypes, the familiar tapered tube forks of the production Series One were finalised. Surprisingly, Moulton decided to put a curve in these fork blades to echo the front forks. He said that people would expect to see forks of this conventional curved profile. There is no doubt that visually, the Series One rear forks are the prettiest design, complementing the frame perfectly and leading the eye in a smooth swoop down the bicycle from front to back. However, it is well known that the forks can crack if treated harshly; the delicacy was taken slightly too far and the testing not severe enough. Moulton blamed the curved tubes and when the forks were redesigned for the Series Two, the curve was eliminated. There's no doubt that Series Two forks are more matched to the loads expected of them, but I've found that some well-located strengthening plates on the Series One forks makes them rigid, and sufficiently strong. In my view the vulnerability to cracking has got more to do with their low resistance to twisting than curves in the blades.

Kingfisher blue was chosen as one of the colours in the range, and far outstripped the other colours in popularity. Most of the Moultons that you will find are painted this metallic blue. Could there have been an Italian influence?

Kingfisher blue was chosen as one of the colours in the range, and far outstripped the other colours in popularity. Most of the Moultons that you will find are painted this metallic blue. Could there have been an Italian influence?

The Spaceframe

Following the intense development period of 1959-1961, the classic Moulton bicycle went into production. Apart from a few detail changes, the design changed little until the Mk3 version of 1969. I must clarify that this is the production Mk3 Moulton, not one of the prototype marks described above. But compared with what we have just looked at, the new triangular rear forks and removable rear carrier are small improvements.

Raleigh, who were by this time making the Moulton and owned the patent rights, did not even want to retool for the cost-conscious version of the Mk3, the Mk4. Click on the photo to see the Mk4 following restoration by Moulton Club Chairman Arthur Smith. It was only after Alex Moulton took the option of terminating his contract with Raleigh that he felt a resurgence of interest in further intensive development of the small wheeled bicycle. For the second time, Raleigh were to repeat the pattern of turning their backs on promising new designs of bicycles.

Raleigh, who were by this time making the Moulton and owned the patent rights, did not even want to retool for the cost-conscious version of the Mk3, the Mk4. Click on the photo to see the Mk4 following restoration by Moulton Club Chairman Arthur Smith. It was only after Alex Moulton took the option of terminating his contract with Raleigh that he felt a resurgence of interest in further intensive development of the small wheeled bicycle. For the second time, Raleigh were to repeat the pattern of turning their backs on promising new designs of bicycles.

Two years were spent trying all kinds of different materials and configurations, looking for an improved frame. Some of the experimental frames were made from aluminum tube, some made from wood. Alex has said that wood is "not at all a silly choice for a frame material". He is very familiar with kayak constructional techniques and must have appreciated how light and rigid a kayak is. The interesting thing here is that Alex was using a kind of guided "natural selection" approach, that is, deliberately introducing curveballs in the form of very unusual shapes and materials. In this way, tests of the experimental shapes may have thrown up positive characteristics that had not been foreseen. Back in 1960, the method seems to be more one of taking an existing idea and refining it. We know that nature evolves animals and plants by introducing unexpected quirks of design that turn out to be more successful than the common variety. Alex seems to be consciously, or unconsciously, adopting this approach.

One very different feature of the new frames is that, even before the spaceframe, he was thinking of the bicycle very much as a three-dimensional object. For example, the original Stowaway joint was subjected to severe torsion tests on a new frame-twisting machine, which it failed, and was given the heavy elbow. This means that he is viewing the forces travelling though the bike diagonally, say from the right end of the handlebar to the left pedal, and the fact that a heavy rear carrier is held upright using the handlebars at the front of the bike. In other words, the whole structure is constantly subject to cyclic twisting. He had solved the new requirements with a Y-shaped frame having a corrugated side (shown third from the left in the photo above). This made the new design of Stowaway joint much stronger torsionally. The new bicycle nearly went into production, but was sunk by a put-down from a Frenchman. Alex decided to look again at the frame design and it occurred to him to return to the small tubes of his original 1959 suspension. At a stroke, it was as if the Moulton bicycle frame burst from black and white into techni-grey.

One very different feature of the new frames is that, even before the spaceframe, he was thinking of the bicycle very much as a three-dimensional object. For example, the original Stowaway joint was subjected to severe torsion tests on a new frame-twisting machine, which it failed, and was given the heavy elbow. This means that he is viewing the forces travelling though the bike diagonally, say from the right end of the handlebar to the left pedal, and the fact that a heavy rear carrier is held upright using the handlebars at the front of the bike. In other words, the whole structure is constantly subject to cyclic twisting. He had solved the new requirements with a Y-shaped frame having a corrugated side (shown third from the left in the photo above). This made the new design of Stowaway joint much stronger torsionally. The new bicycle nearly went into production, but was sunk by a put-down from a Frenchman. Alex decided to look again at the frame design and it occurred to him to return to the small tubes of his original 1959 suspension. At a stroke, it was as if the Moulton bicycle frame burst from black and white into techni-grey.

I'm very happy to credit the owner of this image, Tom Taylor who released it for reproduction under the Creative Commons licence. Please look at this link if you wish to re-use the image.

I'm very happy to credit the owner of this image, Tom Taylor who released it for reproduction under the Creative Commons licence. Please look at this link if you wish to re-use the image.

Getting back to the subject of this page, what were the influences on the design of the spaceframe? One is very obvious: the Dursley Pedersen bicycle of 1899. Mikael Pedersen was an engineering genius; you can read all about his colourful life and achievements here. What he did for the bicycle was tear up the design rule book and start from scratch. Audacity! And design his new frame around a very comfortable sprung saddle. Remember that the roads were very rutted and potholed in those days. As well as springing, the frame uses small tubes and a slightly three-dimensional structure. However, it is nothing like the Moulton spaceframe except for one characteristic; it is completely composed from triangles.

The main thrust of Moulton's work at this stage was to develop a lighter, stiffer frame. If he was going to do this with small tubes, there was no way he could avoid using triangles. A triangle is the most rigid shape in engineering. It cannot be twisted; all the points must always lie in the same plane. Neither can a triangle be skewed into a rhombus like a rectangle can. Triangles are always rigid. Pedersen's bicycle frame weighed less than twenty pounds in an era when engineering was very heavy. This was thanks to his using only the minimum steel to get the strength necessary, but also arranging his slender tubes in the ideal manner to carry the stress. He even made a frame out of wood. Alex must have been fascinated by this and respectful of Mikael Pedersen's superhuman powers of intuitive stress analysis. He has his engineering heroes and Pedersen is certainly included for his great originality.

I wanted a photo of the Dursley Pedersen, but instead found this excellent photo of a Copenhagen Pedersen, a modern interpretation. It shows just how enduring a good design can be. The image belongs to Eva Krocher and is released for copying under the GNU Free Documentation Licence. You can see that the bicycle is not at all unisex- no open frame. The head and seat tube angles are also very shallow. So, there was nothing much that could be transferred to the Moulton small wheel format. But Pedersen also designed and built a ladies frame, and this where you suddenly see the resemblance.

I wanted a photo of the Dursley Pedersen, but instead found this excellent photo of a Copenhagen Pedersen, a modern interpretation. It shows just how enduring a good design can be. The image belongs to Eva Krocher and is released for copying under the GNU Free Documentation Licence. You can see that the bicycle is not at all unisex- no open frame. The head and seat tube angles are also very shallow. So, there was nothing much that could be transferred to the Moulton small wheel format. But Pedersen also designed and built a ladies frame, and this where you suddenly see the resemblance.

If you mentally combine these two frames you end up with something looking very like a side view of a Moulton spaceframe. That is, on the yellow bike, look at the tubes that run diagonally from the rear axle to the top of the steering. Now, imagine that forward of the seat-tube crossing point, the diagonal tubes instead travel horizontally across to the front of the frame and are fixed to the base of the steering. (There is no head tube as such). What you now have is an 'open' frame very like the Moulton. Of course, the Pedersen frame has the hammock saddle and tension cables running vertically from the back axle to the back of the saddle. These need to be removed, which means that the seat tube now supports most of the weight of the rider. A larger diameter tube, or a wigwam, is necessary.

If you mentally combine these two frames you end up with something looking very like a side view of a Moulton spaceframe. That is, on the yellow bike, look at the tubes that run diagonally from the rear axle to the top of the steering. Now, imagine that forward of the seat-tube crossing point, the diagonal tubes instead travel horizontally across to the front of the frame and are fixed to the base of the steering. (There is no head tube as such). What you now have is an 'open' frame very like the Moulton. Of course, the Pedersen frame has the hammock saddle and tension cables running vertically from the back axle to the back of the saddle. These need to be removed, which means that the seat tube now supports most of the weight of the rider. A larger diameter tube, or a wigwam, is necessary.

I may appear to be arguing that the Moulton spaceframe is just a small-wheeled Pedersen. This is not true. but it may well have provided the inspiration to Alex to jump from his large-tube frames shown in the photo above to the small tubes that are now so much a signature of his design. Let us have another look at the photo of those earlier frames. They show very well the true source of the spaceframe.

Although not many of the frames in the photograph seem to separate, in fact Alex had decided by this stage that his new bicycle would definitely be separable. Most of the frames in the group are probably there to find the ideal balance of light weight and good torsional rigidity. Each one would have been put through a tussle with his new frame twisting machine. The designs having two tubes would obviously need two joints in order to separate, and that would have added weight. Note that all the tubing is of a wide diameter. The second frame, interestingly, has a removable top tube. His corrugated Y-frame incorporated a single joint and weighed 4lb 11oz (2.13kg); less than the Raleigh Mk3 frame with no separating facility. So, it was definitely the front runner. One other frame had been fitted with a joint, but it used a large bulky ring. Remember that Moulton's designs must be delicate to satisfy him.

The three frames on the right, particularly the one on the far right, show the tendancy towards widening the tube in the centre of it's span. It is approaching the idea of being vertically wide at the seat and head tubes and horizontally wide in the centre, which suggests the shape of a covered spaceframe. What I mean is that it is like the curved main part of my cardboard monocoque, which is also based on the spaceframe. Not at all easy to separate at the mid-span however, without a serious weight penalty.

The three frames on the right, particularly the one on the far right, show the tendancy towards widening the tube in the centre of it's span. It is approaching the idea of being vertically wide at the seat and head tubes and horizontally wide in the centre, which suggests the shape of a covered spaceframe. What I mean is that it is like the curved main part of my cardboard monocoque, which is also based on the spaceframe. Not at all easy to separate at the mid-span however, without a serious weight penalty.

So, there was only one other contender to the Y-frame and that was the X-frame fifth from the left. It could have incorporated a single separating joint at the crossing point. This idea must have made it very attractive to Alex. And it was not very heavy, only 3lb 3oz. The twisting machine must have finished the large-tube X-frame concept. These frames do show well that to satisfy the criteria for the new bicycle, the frame shape should be narrow in the centre for single-joint separability, but at the same time wide in the centre for good torsional rigidity. These are contradictory requirements that can't be solved by a big-tube design. It was this research and development that led to using a lattice of small-bore tubes.

Pedersen was not thinking about separating his bicycle when he designed it. His focus was not on a dividing point in the centre of the frame. He was not concerned overly about torsional rigidity. What he wanted to do was make as lightweight a machine as possible using the primitive steels (or wood) available at the time. And combine this with the greatest comfort, achieved using his original sprung hammock saddle. I think of his bicycle as being like the Citroen 2CV of the velocipede world. Quirky, yet years ahead of it's time. Amazingly comfortable on bad roads. Weighing as little as possible. Technically advanced, with Pedersen's own 3 speed hub gear. Usable today, a hundred years after it's invention. But I don't think that it was as important to the spaceframe as Alliot Verdon-Roe's cross-frame bicycle was to the classic Moulton.

Interestingly, this photo of the first prototype spaceframes shows that the first design, far left, did not even have a lower tie tube. It was an X-frame very like the first, but this time only horizontally wide at the centre. Alex had combined the two contradictory virtues of low-weight separability and torsional stiffness by minimising the size of the separating point in the vertical plane, and widening the size across the frame. I realise that sounds brain-bending.

Interestingly, this photo of the first prototype spaceframes shows that the first design, far left, did not even have a lower tie tube. It was an X-frame very like the first, but this time only horizontally wide at the centre. Alex had combined the two contradictory virtues of low-weight separability and torsional stiffness by minimising the size of the separating point in the vertical plane, and widening the size across the frame. I realise that sounds brain-bending.

The important point is that the spaceframe was clearly derived from incremental modifications of the original F frame. We may think of the spaceframe as being an entirely new idea, from outer space, but in fact it was essentially only one small step from the big tube X-frame to the small-tube X-frame. It is a supreme demonstration of how evolution can produce what seems like a new species. The very latest Moulton bicycles can be traced to the Pininfarina working backwards through the innovations.

This photo-sequence of spaceframe prototypes shows how slowly and carefully the development carried on; over two years to make a few small changes. In August 1977 there seems to be a separating joint fitted in to the structure, but also lugs around the headtube. It took considerable work to develop the machinery and jigs necessary to shape the tube ends for lugless brazing. Alex decided to put the bicycle into production in November 1979.

Tony Hadland's excellent book "The Spaceframe Moultons" was consulted during the writing of this page. The frame photographs were scanned from the book. My thanks go to him for such a detailed account. "The Spaceframe Moultons" is highly recommended and you can buy a copy via the Waterstones page here.

Suspension methods

It is very interesting that the accepted genesis of the Moulton bicycle runs as follows: 1. Decided to create a small wheeled bicycle. 2. Made prototype and tried it, but found vibration unacceptable. 3. Created suspension systems to get around problem; hey presto, a comfortable and efficient new bicycle. But we know that the monocoque was the first Moulton bicycle prototype, and it was made with suspension on the front. It's unclear whether it has suspension on the rear. What this means is that Moulton was definitely planning to use suspension on the bicycle before he had even started making prototypes. Well he would, wouldn't he? He had just finished several years work on the suspension of the Austin Mini. He knew very well that small wheels would be more affected by the micro-terrain of the road surface. I think that from the outset Alex wanted to develop some new suspension systems for the bicycle that would use rubber as the spring medium. Nothing had been done in this area up to that time.

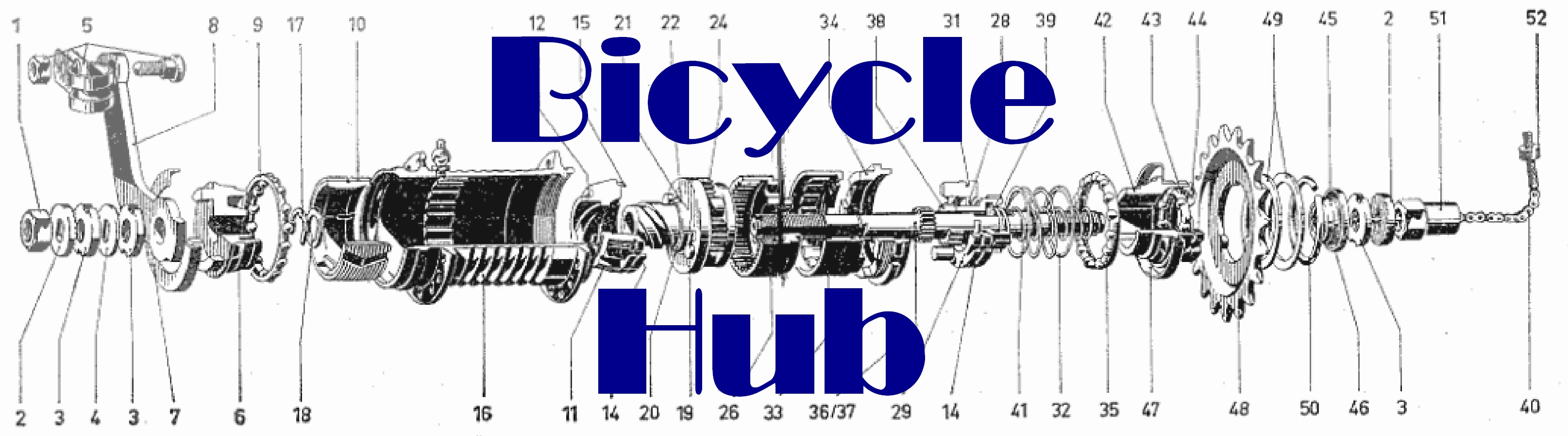

Alex Moulton's expertise in the rubber business was the patented technique of bonding rubber to metal. This enabled him to design suspension that could deform the rubber in new ways, not simply just in straight compression. First there were his Flexitor trailer suspensions that used a rubber annulus bonded to an internal and external tube. Keeping one tube fixed whilst rotating the other created a sort of rotating spring. This will be seen further down the page. In a miniature form, this is exactly the method used on the front suspension of the "New Series" Moultons, and their rear triangle pivot bushes. The series' one and two Moultons had a curved rubber sandwich at the back, both squeezed and stretched in shear by the action of the rear forks. The rubber sandwich was bonded to two metal plates (performing as the slices of bread) and the plates fastened to the frame and forks. This sophisticated technique meant that the suspension became stiffer when more weight was put onto it, so it worked just as well under a wide range of loads. You can see the workings of this suspension on my assembly page here.

I have already described the classic Moulton front suspension further up this page, but if you want to see the animal in the flesh, have a look at my assembly page here. After Raleigh had given up interest in the Moulton Mk3 there was a parting of the ways, and Alex, although free to use certain aspects of the original concept, does not appear to own rights to the classic rubber front suspension. It may be that he wanted to make some improvements or simplify the design a little. Either way, with the spaceframe a new front suspension emerged. I say "new" but the methods used on the AM and the New Series were all adapted from pre-war motorcycles.

Alex Moulton loved motorcycles, we know that. Before the war, he must have had a huge interest in any motorcycle he saw passing in the street. None of them had the telescopic suspension forks that are so familiar to us today. They most commonly used a separate "floating" fork attached to the steering with two pairs of links. Indeed, in a very similar way to the New Series Moulton. Of course, the motorbikes did not benefit from torsional rubber spring elements like the New Series. They had thumping big steel springs. What Moulton managed to do was to take an elegant idea from the past, blend it with his own technology and produce something quite new.

To the left is a Chater-Lea motorbike designed for racing. Chater-Lea were a manufacturing company based in London with a reputation for very high quality machinery. I guess that Alex was a Chater-Lea enthusiast, as his suspensions seem to echo powerfully those of this particular pre-war motorcycle builder. It's of relevance that Chater-Lea made excellent bicycles as well. Compare this motorbike's front suspension with the spaceframe's. It has leading links at the fork blade ends that appear to use friction disc dampers. The stirrup is much smaller and more delicate than the main fork, has completely straight blades and a rounded top like a large paper-clip.

To the left is a Chater-Lea motorbike designed for racing. Chater-Lea were a manufacturing company based in London with a reputation for very high quality machinery. I guess that Alex was a Chater-Lea enthusiast, as his suspensions seem to echo powerfully those of this particular pre-war motorcycle builder. It's of relevance that Chater-Lea made excellent bicycles as well. Compare this motorbike's front suspension with the spaceframe's. It has leading links at the fork blade ends that appear to use friction disc dampers. The stirrup is much smaller and more delicate than the main fork, has completely straight blades and a rounded top like a large paper-clip.

The brakes are fixed to the stirrup. Even the main forks have completely straight fork tubes. There is one main spring in the centre at the top of the stirrup, but unlike the AM, the Chater-Lea's spring is not concealed withing the steering tube. Conceptually though, the two systems are very similar.

The brakes are fixed to the stirrup. Even the main forks have completely straight fork tubes. There is one main spring in the centre at the top of the stirrup, but unlike the AM, the Chater-Lea's spring is not concealed withing the steering tube. Conceptually though, the two systems are very similar.

New Series front suspension

Here's one of the latest Alex Moulton bicycles, the New Series. Although the entire frame was re-designed to incorporate larger wheels, 406 in place of 359, and pack into a suitcase, the principal change was the completely new front suspension. Moulton cleverly adapted his Flexitor torsional springs first used in BMC's Land-Rover competitor, the Austin Gypsy, to float the entire front fork. The Flexitors were miniaturised and fitted into the hinge pins of the two pairs of connecting rods.  There are great advantages to this design. The suspension has no "sticktion", that is, resistance to movement until a threshold is exceeded. The high frequency vibration is isolated from the rest of the frame by the rubber in the Flexitors. And there are no parts that can wear, as the rubber annulus separates the moving adjacent surfaces, like the inter-joint material in your knees and hips. It must have pleased Alex greatly to return to rubber as a suspension medium after all those years of the pogo spring of the AM. And the ride quality of the New Series is on a higher level altogether. Even over a cobbled road, the New Series floats like a kind of hovercraft.

There are great advantages to this design. The suspension has no "sticktion", that is, resistance to movement until a threshold is exceeded. The high frequency vibration is isolated from the rest of the frame by the rubber in the Flexitors. And there are no parts that can wear, as the rubber annulus separates the moving adjacent surfaces, like the inter-joint material in your knees and hips. It must have pleased Alex greatly to return to rubber as a suspension medium after all those years of the pogo spring of the AM. And the ride quality of the New Series is on a higher level altogether. Even over a cobbled road, the New Series floats like a kind of hovercraft.

A very charming feature of the suspension is that the arrangement of two pairs of hinged rods was used on motorcycles over a hundred years ago. There is no secret to this; most motorcycles employed the same technology.

Aerial, with friction disc damping

Aerial, with friction disc damping

Alex Moulton may have brought back the look of the old technology in a consciously nostalgic way; in fact, he has stated as much. Royal Enfield were based in Redditch, but also had a factory in Bradford-on-Avon. This must have excited the young Moulton, especially if he saw the machines roaring up the hill past the Hall. In a neat symmetry, Royal Enfield are still in business and the factory is about 12 miles from Stratford-on-Avon, where the Moulton TSR spaceframe is made.

One noticeable feature of the New Series link-arms is that the pairs of rods are not parallel. The lower set have a larger angle to horizontal than the upper set. This means that when the suspension is compressed, the front wheel is pushed out forwards. The idea is that when the brakes are applied sharply, the force pushing against the wheel from the road acts through the suspension geometry and prevents the front of the bike "diving". It is a brilliant feature- designed in the 1920's by Chater Lea.

One noticeable feature of the New Series link-arms is that the pairs of rods are not parallel. The lower set have a larger angle to horizontal than the upper set. This means that when the suspension is compressed, the front wheel is pushed out forwards. The idea is that when the brakes are applied sharply, the force pushing against the wheel from the road acts through the suspension geometry and prevents the front of the bike "diving". It is a brilliant feature- designed in the 1920's by Chater Lea.

This beautiful machine is in the "Milestones" museum in Basingstoke. It was the AA's patrol bike of choice in the early 20th century. You need to look closely to see the upper link arms because they are painted black. Note also the large springs that perform the function of Moulton's Flexitors. A motorcycle has a lot more mass than a bicycle, and it travels much faster. I once had the good fortune to look around the small factory at Bradford-on-Avon when the New Series was first made. I was amazed to see from a cross section of a Flexitor spring that it contained such a thin annulus of rubber, only about as thick as an inner tube.

It is interesting that the original twin link bar front suspension of the motorcycle is now almost forgotten. Perhaps this is because the second world war separates us from the design, and post-war motorcycles all seem to have the springs and shock absorbers within the fork tubes. Moulton had been alive for a long time, and has seen many different technologies come and go. He was able to search through his mental stores and select something seemingly redundant to incorporate into the latest range of his bicycle. Very few other designers would have been able to do this. I think that it is remarkable how a system from the dawn of motorcycles combined with a torsion spring from the 1950's should, when blended together, produce a sophisticated 21st century bicycle suspension.

It is interesting that the original twin link bar front suspension of the motorcycle is now almost forgotten. Perhaps this is because the second world war separates us from the design, and post-war motorcycles all seem to have the springs and shock absorbers within the fork tubes. Moulton had been alive for a long time, and has seen many different technologies come and go. He was able to search through his mental stores and select something seemingly redundant to incorporate into the latest range of his bicycle. Very few other designers would have been able to do this. I think that it is remarkable how a system from the dawn of motorcycles combined with a torsion spring from the 1950's should, when blended together, produce a sophisticated 21st century bicycle suspension.

Conclusions

As this page has grown into the size of a mini book, it seems fitting to wrap it up with a tidy conclusion. Alex Moulton will always be regarded as the engineer who designed the small-wheeled bicycle. It is thought that the name "Moulton", used as a generic term for small-wheelers, contributed to his original bicycle's reputation becoming tarnished by association with inferior machines. But Moulton wasn't the originator; Le Petit Bi of 1946 was a French folding bicycle with wheels of roughly 16" diameter. The idea of minimising size and making machines lighter in weight is a natural course of action for a designer.

Moulton's outstanding contribution to bicycle design was his re-invention and enhancement of the machine's function. That is, the combined virtues of rubber suspension, open frame, small wheels and integral carrying capacity. All these aspects are essential and have a holistic value, the whole being greater than the sum of the parts. Without the suspension, the small-wheeled ride quality would have been unacceptable. Without the small wheels, the low main beam and flat, wide rear carrier would be impossible. Without the open frame, the ease of use would be no better than a diamond frame big-wheeler. This multi-faceted concept had no fore-runners and few serious imitators. The fact that the Moulton bicycle also looked like a beautiful object was a useful bonus, due in no small part to the design hothouse that Britain was in the 1960's.

It is important to appreciate the context into which the Moulton Bicycle was born. It arrived at a time of tremendous confidence, the Post-War dream, the NHS, the white-heat of technology, Ladybird books, television and high-rise living. Designers were looking to the future and spurring each other on. Society was becoming more egalitarian and meritocratic. It was a brave new world. Alex Moulton has always belonged to this world, confident of his engineering views and ability. All of his bicycles reflect these times; faster, modern-looking, comfortable, user-friendly and technologically advanced.

It is important to appreciate the context into which the Moulton Bicycle was born. It arrived at a time of tremendous confidence, the Post-War dream, the NHS, the white-heat of technology, Ladybird books, television and high-rise living. Designers were looking to the future and spurring each other on. Society was becoming more egalitarian and meritocratic. It was a brave new world. Alex Moulton has always belonged to this world, confident of his engineering views and ability. All of his bicycles reflect these times; faster, modern-looking, comfortable, user-friendly and technologically advanced.