The Demise of the Classic Moulton

There are different reasons and several viewpoints as to why production of the classic Moulton bicycle came to an end in 1974. It seems crazy on the face of it; a much improved design that had been so successful, scrapped off. Was it for reasons of fashion? Was it due to the reluctance of bicycle dealers to stock it? We may never have a definitive answer. Here are two viewpoints, both mine. The first was based on the tablets of wisdom handed down from on high. The second fermented after Alex Moulton's talk at the 2004 Bradford-on-Avon Moulton meet.

The turncoat cycle dealer theory

The startling originality of the Moulton bicycle is difficult to appreciate in the 21st century. Since its launch, there have been many variations upon bicycle design, particularly in the style of the frame and materials used. Modern mountain bikes, for instance, seem so radical in their frame design that beside them, the Moulton looks ordinary. Shopping bikes, folding bikes and the Raleigh Chopper have all diluted Moulton’s ‘F frame’ small-wheeled bicycle innovation, the first design that successfully broke away from the eighty year old diamond frame concept.

If there is anything that a young person will notice about my Moulton, it is the 16” wheels, which usually provoke laughter. A Moulton mini, having 14” wheels, sets off gales of derisive laughter (the smaller the wheels, the greater the ridicule, obviously). Looking closer, they might see the suspension working. This often sparks interest, because modern mountain bikes have suspension, and there is a reflected coolness. And it proves that when the minds of the young are actually engaged, the design begins to be interesting. There might be a good reason for small wheels after all.

With great ingenuity, the Moulton's front suspension was entirely contained inside the steering column, only a rubber bellows above the forks giving away the invention. A long steel spring wrapped around a coil of rubber was fitted inside the steering tube, held at the base by the brake bolt. The quality of the front suspension depended on the characteristics of this main spring. Different compounds of rubber were made available to alter the stiffness, depending upon whether the bike was a utility or a sports model. Upon compression, discs of rubber were squeezed between the spring coils to give a nicely damped system. To absorb rebound shock, a further small spring was fitted above the main suspension spring.

With great ingenuity, the Moulton's front suspension was entirely contained inside the steering column, only a rubber bellows above the forks giving away the invention. A long steel spring wrapped around a coil of rubber was fitted inside the steering tube, held at the base by the brake bolt. The quality of the front suspension depended on the characteristics of this main spring. Different compounds of rubber were made available to alter the stiffness, depending upon whether the bike was a utility or a sports model. Upon compression, discs of rubber were squeezed between the spring coils to give a nicely damped system. To absorb rebound shock, a further small spring was fitted above the main suspension spring.

Such a sophisticated suspension might be expected to be expensive, but the Moulton bicycle was not beyond the reach of ordinary cyclists. It was comparable in cost to other quality bicycles on the market, a great achievement. Where the Moulton’s revolutionary suspension system foundered was in ease of maintenance; it was relatively difficult for the average cycle mechanic to work on. Access to the cross-head screw holding the front unit together was inordinately difficult, as it was located at the end of a long, narrow, dark tube. Due to dirt accumulation and rust from condensation, the screw was often too solidly stuck, which caused the cross-head to be damaged by people who could not easily see what they were doing.

Although a well-lubricated front suspension would remain trouble free for ten or twenty years, lack of the appropriate grease during manufacture allowed rusting of the internal springs and sliding surfaces, with consequent spine-tingling squeaks, early wear of the nylon bearings and roughness. Sadly, most of the bicycles built at the BMC car plant at Kirkby were lacking in care and attention.

If either the build-quality control or the maintenance problem had not existed, the other would not have mattered, but taken together, they spelled the end for the bike. In the absence of clear dismantling instructions, owners often poured ordinary oil down the forks, degrading the rubber column and ruining the suspension stiffness. Bicycle shops began to be reluctant to stock Moultons, mostly because of the servicing difficulties.

Although the original Moulton Bicycle does not appear as familiar these days as it’s inventor may have wished, it did mark a step-change in the thinking of all bicycle companies and generated a whole industry of copycat designs. Perhaps this is why the Moulton hardly appears unusual to people today. Alex Moulton’s strength as a designer was a great ability to combine his wide engineering knowledge with his intuitive design flair, favouring a practical, no-frills approach.

Despite his insistence upon high efficiency and ‘function-first’, his designs do seem to have inherent beauty. Having a very rounded engineering experience, he was able to pull in ideas from many other areas, and knowledge of engineering materials, and use these in an entirely new way. Coupled to these qualities was a determination to persevere despite many obstacles, technical problems and frustrations. Overall, it is the quality of his ideas that endures, and of course, the actual quality of the machines themselves.

The following article was written for the Moulton Club Magazine back in 2004. This was the first draft, and in fact I completely changed half of it before sending it to the Editor. The reason was that it had a slightly cheeky tone that I thought might annoy Dr. Moulton. In retrospect, I think that it captures something of the remarkably candid speech that he made in 2004 about the Mk3 and the end of the F frame Moulton design at Raleigh's hands. It was the most interesting talk I have ever heard at the Bradford-on-Avon Annual Meet. This being so, here is my original article.

The RSW: Was it really so bad?

If you went to the recent Bradford-on-Avon Rally you’ll know that the focus of interest was the Moulton Mk3, 2004 being the 30th anniversary of Raleigh ceasing production of this, the ultimate incarnation of the Classic ‘F’ frame models. A row of around 15 superb Mk3’s were lined up in the stable-yard, sparkling in the bright sunshine, with Doctor Moulton and Shaun seated behind and Tony Hadland expertly taking the role of M.C. In recent years, where BoA has a theme, Alex usually gives a lively and interesting talk during the afternoon. Little could we guess that this year’s topics would develop in such an exceptional way.

We began with a hugely entertaining story of the life and times of Daved Sanders’ Mk3, now a beautifully tuned minimalist touring bike in duck-egg-blue. With great wit, Daved told of sustaining eighty-four punctures simultaneously, as well as modestly underplaying some arduous Audax-style rides (e.g. Windsor-Chester and back, and Paris-Harrogate). Other Mk3 owners followed this tour-de-force as best they could by showing their own machines. Then it was time to examine the design itself, comparing it to the pure form of Arthur Smith’s stripped down Series 1 Woodburn replica. And things began to get even more interesting.

In the back of our minds always was the untimely demise of the Classic Moulton, and also the fact that the Mk3 was a Raleigh-built machine. Various theories have been put forward, but nobody can really produce solid evidence for the Mk3’s failure to find buyers. Raleigh’s manufacturing capability has declined dramatically in recent years and they no longer even make their own frames, whilst their subsidiary, Sturmey-Archer, were tricked by a vulture-like finance company and suffered the indignity of asset-stripping. One could not help seeing this in the context of the decimation of British manufacturing in the last thirty years. When any questions about the Mk3 were invited, I very nearly asked Dr. Moulton what his feelings were about Raleigh dropping the Mouton, but tactfully refrained. This was good, because my question was answered in spadefuls in any case.

Alex began with customary dry wit by describing Raleigh’s insistent cost-cutting measures, which inevitably downgraded what should have been the greatest version of the F frame Moulton. This emphasis, he asserted, was entirely the wrong direction. Although great respect for Raleigh’s manufacturing capabilities was felt, Alex was always opposed to the company exerting their power of ownership by diluting the design, and cheapening the components. (Aynsley Brown’s Mk4 showed this to great effect, with its ‘Raleigh-ised’ curved swan-neck stem.)

Alex began with customary dry wit by describing Raleigh’s insistent cost-cutting measures, which inevitably downgraded what should have been the greatest version of the F frame Moulton. This emphasis, he asserted, was entirely the wrong direction. Although great respect for Raleigh’s manufacturing capabilities was felt, Alex was always opposed to the company exerting their power of ownership by diluting the design, and cheapening the components. (Aynsley Brown’s Mk4 showed this to great effect, with its ‘Raleigh-ised’ curved swan-neck stem.)

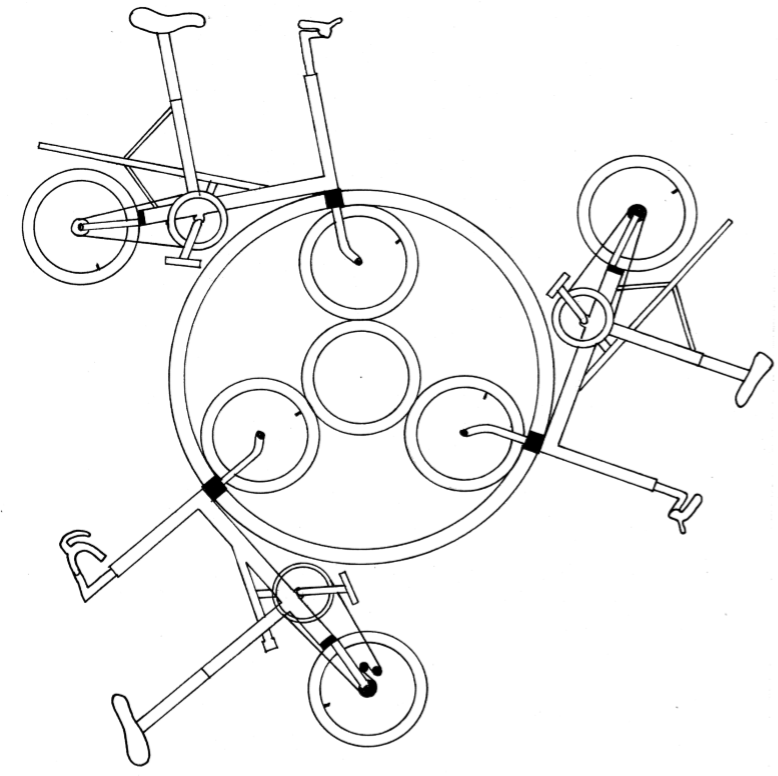

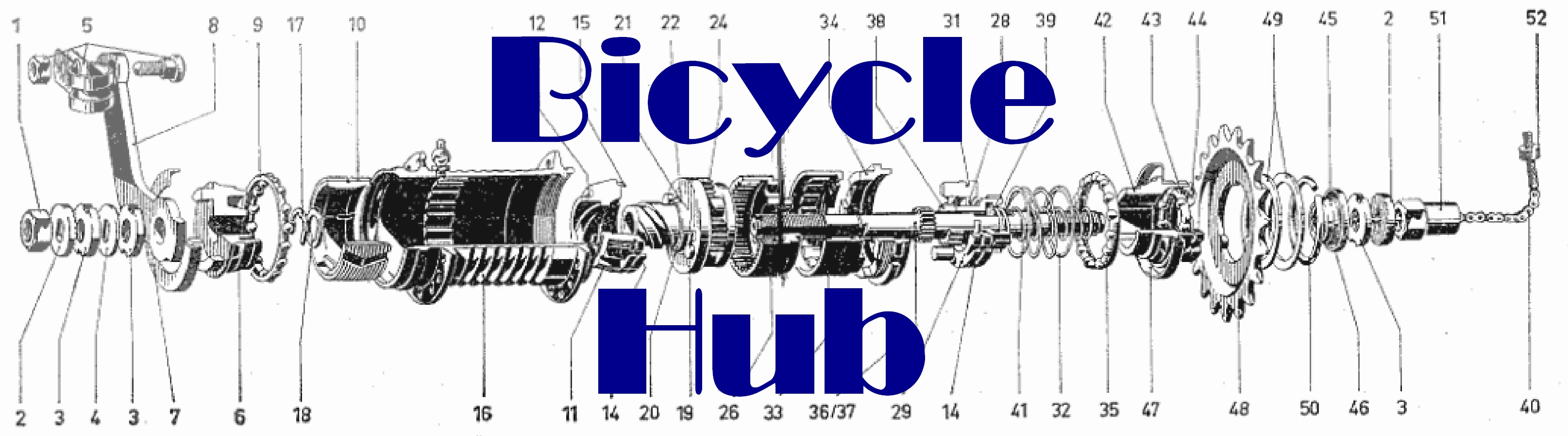

One can imagine the colourful arguments that must have occurred in Raleigh’s boardroom and at The Hall during the 1970’s. These men knew each other well and were accustomed to straight talking. Alex betrayed some bitterness when Tony asked him about the non-negotiable fitting of the useless S3B drum-brake 3 speed. “I took the view that it was their bike and they should be allowed to select the hub gear,” he answered shortly.

In the last issue of the Moultoneer we were treated to the fascinating article revealing two dusty prototype Mk3’s, photographed outside for the first time since the late 1960’s. They are clearly part of Alex’s vision of the forthcoming bike. One model had a specification something like Colin Martin’s Marathon, with ‘Stowaway’ style separable joint but also a full set of derailleur gears. The other was similar to the actual production Mk3 except for the gearing, which was, excitingly, a far better five speed hub. We can also fondly imagine a racing version not dissimilar to Vic Nicholson’s, machine which he rode in the Bristol South ‘25’ winner’s reunion in 1981 (Page 75, The Moulton Bicycle). There was no way that Alex would have wanted the S3B within 500 miles of the production bike. Neither did he approve of the heavy solid steel bar/stand, welded to the bottom bracket. “I would not have designed it like that in a thousand years.”

In the last issue of the Moultoneer we were treated to the fascinating article revealing two dusty prototype Mk3’s, photographed outside for the first time since the late 1960’s. They are clearly part of Alex’s vision of the forthcoming bike. One model had a specification something like Colin Martin’s Marathon, with ‘Stowaway’ style separable joint but also a full set of derailleur gears. The other was similar to the actual production Mk3 except for the gearing, which was, excitingly, a far better five speed hub. We can also fondly imagine a racing version not dissimilar to Vic Nicholson’s, machine which he rode in the Bristol South ‘25’ winner’s reunion in 1981 (Page 75, The Moulton Bicycle). There was no way that Alex would have wanted the S3B within 500 miles of the production bike. Neither did he approve of the heavy solid steel bar/stand, welded to the bottom bracket. “I would not have designed it like that in a thousand years.”

Alex spoke with a curious mixture of respect towards Raleigh for taking the bike on, tempered by disappointment at how it had developed because of their wrong-headed penny-pinching policy. We gained a fresh insight into the complex relationship between a creative designer and the controllers of his work. Underlying all was a persistent regret for the “deeply sad” loss of British Manufacturing in general, and vehicle-making in particular, which was illuminated by an aside describing car suspension work for B.M.C.

So how had Raleigh managed to lose the vision of the Moulton as the improved bicycle, put forward so perfectly by Alex in the two prototypes, and confirmed to great effect by Colin Martin and Daved Sanders? Answer; one big fat arrow-wedge reason- The Chopper. “They were besotted with it. They were completely obsessed by it,” revealed Alex disdainfully. This was sensational. It cast the whole endgame in a different light. The Chopper was fantastically successful for Raleigh, and quite out of the blue. As a result, the company altered its mindset, beginning to see all bicycles as profitable toys. This view holds water. We know that the launch of the Chopper, the RSW III and the Mk3 was simultaneous, accompanied by the slogan “A bicycle is not just a plaything.” Who were they trying to convince, the public or themselves? Hopefully, this will be expanded upon in Dr. Moulton’s autobiography!

We have always believed the plausible story that the Classic Moulton became confused in the public’s mind with cheaper, copycat small wheelers and folders, having inferior riding characteristics. For the lay-person understanding nothing of tyre pressure, rolling resistance and gearing, it is an easy-to-assume idea; ‘small wheels mean slow speeds and hard work’. Without doubt there is a chief villain; fat-tyred King of Energy-Sapping, the RSW. Made by Raleigh. Launched on the same brochure as the Moulton. Eh? We have to ask ourselves anew whether the RSW and its creaky fellows really did seal the Moulton’s fate. Was the RSW really so bad? For several reasons, the assumption does not add up. Why would Raleigh deliberately self-sabotage the launch of the Mk3 by associating it so closely with “The Dolly One”? And after taking on the Moulton, why did Raleigh not delete the RSW model, if it was so inferior?

We have always believed the plausible story that the Classic Moulton became confused in the public’s mind with cheaper, copycat small wheelers and folders, having inferior riding characteristics. For the lay-person understanding nothing of tyre pressure, rolling resistance and gearing, it is an easy-to-assume idea; ‘small wheels mean slow speeds and hard work’. Without doubt there is a chief villain; fat-tyred King of Energy-Sapping, the RSW. Made by Raleigh. Launched on the same brochure as the Moulton. Eh? We have to ask ourselves anew whether the RSW and its creaky fellows really did seal the Moulton’s fate. Was the RSW really so bad? For several reasons, the assumption does not add up. Why would Raleigh deliberately self-sabotage the launch of the Mk3 by associating it so closely with “The Dolly One”? And after taking on the Moulton, why did Raleigh not delete the RSW model, if it was so inferior?

The clues are in the equipment fitted to the two bikes. They are virtually identical in specification. Moultoneers know that the Mk3 can look exciting; many owners correctly seeing the underlying character have modified them beautifully. Potentially, the design could out-Galaxy the Dawes Galaxy as a touring machine. Yet it is difficult to imagine the actual production version going any further than the supermarket, never mind Australia. Raleigh seemed to have held an identical vision of both the RSW and Moulton. One could argue that Raleigh as a company had a certain way of making things, strong but utilitarian, and they made everything in the same way. Bring to mind the “Twenty” and the “Wayfarer” and you will know that seventies style. It is not the style of a serious quality, lasting machine.

Perhaps, blinded by the Hot success of the outlandish Chopper, Raleigh’s design bosses regarded both the Dolly and the Smooth ones as dated, unfashionable products. We should recall that the mood and style of the country shifted markedly and rapidly at the turn of the decade. In the Moulton, Raleigh had taken on an exotic, highly-developed machine, the frame and forks strong and rigid, yet weighing less than 11 pounds. More than ever before it was capable of a multitude of diverse roles and suitable for a wide range of sizes. They turned it into a superficially mundane utility bicycle. This is a form that even today, in this Club, not many people really like as original, as evidenced by the parade at BoA. Is it possible that the Moulton, such a powerful 1960’s fashion icon, simply appeared too ordinary in the 1970’s and so went out of fashion?

Looking at the brochure and that evocative Dolly-Hot-Smooth One advert, we can see the hopeless attempt at conveying the Moulton’s character. The Dolly One is straightforward enough, slim young girl having a fun time. Like the girl, the tyres aren’t even all that fat anymore. All kids loved the Hot One more than their own family; its irresistible. But if that character sitting next to the Smooth One is, like the Guinness man, supposed to be the living embodiment of the bike, then I know where I’d like to “pack a GT punch”. Where is he going to ride his bike; the jazz club? a cocktail bar? You can just see him scrubbing at an oily chain-mark on those white trousers the morning after.

I cannot help but defend the RSW, not as an equivalent to the Classic Moulton, but more as a nostalgic reminder of such a defining style period. It seems like the last time society in Britain was cohesive and actually happy. The RSW doesn’t want to go round the world, or race between London and York, and its not trying to kid you that it does. As a simple method of overcoming Alex Moulton’s suspension patents, large pneumatic tyres are not a bad idea on such a bike. I’m sure John Boyd Dunlop would see the low unsprung mass and high-frequency vibration absorption advantages straightaway. And considering that the tyres are specially-designed light nylon, some thought has been given to hysteresis loss in the ‘rubber’. Perhaps it is time to forgive, build bridges and invite our guest speaker next year. May I introduce Louis Jongleur.

Lewis Jongleur was the bumptious Chairman or President of the rival RSW Club, who has at times appeared in the magazine requesting a merger with the Moulton Club. Their club magazine has the title "Fat Tyre Facts".